Well well well, we’re into the final couple of months of 2017. Time flies when you’re having fun and all that.

A pretty quiet week this one, so this WNR shouldn’t take too long to read.

![]()

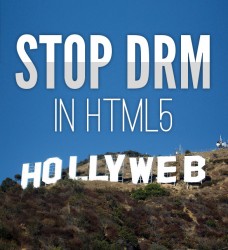

The inevitable has happened and the W3C has formally ratified Encrypted Media Extensions (EMEs) as an official, but voluntary part of the HTML specs. For those not keeping score, EMEs are really just a fancy word for DRM, the type of DRM used by Netflix and Amazon and others to protect their streaming content in browsers such as Chrome and Firefox.

Adding DRM to the HTML standards was always going to be controversial (as our previous coverage on this has demonstrated), and there was always going to be blowback when (and not if) the W3C formally adopted EMEs. The specific blowback this time being the EFF resigning from the W3C to protest not only the decision to include the “terrible idea” of DRM in HTML, but also for not adding in legal exemptions (to deal with anti-circumvention laws) to allow security research.

It’s easy to see why the W3C caved to the demands of the entertainment industry. The World Wide Web, that is the web as we access regularly via our web browsers (and usually rendered via HTML), has been declining in relevance due to the increasing popularity of apps. Most people do not use a browser to watch Netflix, but instead do it via an app. By not having DRM support built into the HTML framework, there is even less incentive for the entertainment industry to continue to allow their content to be streamed via browsers, which is often less secure (in terms of content protection) than their app counterparts (in no small part due to the security by obscurity principle).

But by not allowing a legal exemption for the hacking and cracking of EMEs by security researchers though (and again, probably at the behest of Hollywood interests), EMEs could, as the EFF argues, become a point of attack for hackers with malicious intent and, ironically, make it less secure when it comes to protecting content. The Chrome EME bug didn’t as much go undiscovered for years, as being discovered but not shared due to the fear of legal repercussions by security researchers. The same could happen again, and it would be a further blow to the relevancy of browsers if that happens.

The frustrating thing is that it’s the DRM requirements that’s been making browsers less and less relevant when it comes to streaming video – when playing Netflix 4K content requires a PC that even the most hardcore PC gamers don’t have access to, you know something is not right.

![]()

Apple’s support for 4K on the updated Apple TV puck won’t go as far as to allow offline viewing. While you can download HD and even HDR versions of movies, you can’t do the same for 4K content. Part of the reason for this is the sheer size of 4K movies, but I wouldn’t be surprised if DRM plays a role in this too.

The Apple TV 4K, unfortunately, also won’t support YouTube 4K, a victim of the incredibly tedious video codec wars. The Apple TV supports H.265, but YouTube uses the open source VP9 codec for its 4K content.

Still staying with news about the recent Apple product refreshes, Netflix HDR support will be coming to the iPad Pro, and all of the new iPhones (8, 8 Plus and X).

======

That’s it for this week. See you in seven!