A week after the start of my combined Netflix and Hulu Plus experience, it has already changed the way I consume media. So much so that I actually rang up my cable provider this week and reduced my subscription to a cheaper package, since it turns out that apart from live sports, I’ve not watched a single thing on cable since I started my week’s trial. I also realised that there were tons of DVDs and Blu-rays that I probably would have never bought if I had Netflix all this time. Not to say that Netflix has all of the movies I want, far from it, but there were definitely discs that were impulse buys for me, including ones I purchased more than two years ago and have yet to watch, that could have been better enjoyed via Netflix.

Interestingly enough, there are a couple of Netflix related news this week as well. Let’s get started.

If there’s one thing that really confuses Hollywood, it’s the distinction between BitTorrent, the transfer protocol, BitTorrent, the company, and the BitTorrent that people refer to when they’re downloading tons of pirated movies and TV shows. To Hollywood, the three are synonymous.

Which is why by following the same reasoning, Hollywood should also declare HTTP to be illegal and “evil”. Because equating the three separate entities/acts above would be like equating HTTP, the transfer protocol, with Mozilla, the company that makes a popular software for the protocol, and the act of downloading pirated movies using HTTP from the web.

Release the hounds: Hollywood attacks indie studio for making a deal with the “devil”, BitTorrent Inc

So no surprise then when that the Hollywood attack hounds were released the instant indie film studio Cinedigm struck up a marketing deal with BitTorrent Inc to promote its new movie Arthur Newman. Calling the deal “a deal with the devil” and accusing Cinedigm of selling out for a bit of attention for its new Emily Blunt, Colin Firth flick, a studio exec who spoke to The Wrap anonymously also accused BitTorrent Inc for being “in it for themselves” as “they’re not in it for the health of the industry”.

So if a tech company doesn’t do everything for the health of the film industry, then they’re the bad guys? Well, that does explain why Hollywood has declared war on tech companies and the Internet in general.

Hollywood can either continue their war against a file transfer protocol, as silly as that sounds, or they can wake up and realise that, um, they’re IN A WAR WITH A FILE TRANSFER PROTOCOL!!

If people weren’t using BitTorrent to share files quickly and efficiently, they’d be using some other protocol to do it. And if legal content was available via this or other transfer methods, and at a price and package that’s reasonable, people will use it too.

Just like how it’s far easier to find something classic or obscure to watch on Netflix than to scour BitTorrent indexes for hardly seeded torrents. And that’s exactly why Netflix is doing more every second to stop illegal BitTorrent downloads than anonymous Hollywood execs bitching about a bloody transfer protocol.

According to Netflix’s Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, whenever Netflix moves into a new territory and its popularity increases, BitTorrent traffic in the same region goes down too. It just goes to show that “good value and legal” can indeed compete with the “free and illegal”, especially if you can improve upon convenience. Whatever you say about the decreasing quality and quantify of Netflix content, for $8 a month, it still represents terrific value, and from a convenience point of view, it is hard to beat (compared to finding an active torrent, waiting for the download, maybe further processing to get it to work on the playback device, and then needing the storage capacity to permanently keep a library of downloads, most of which you’ll probably only ever watch once).

You can reduce the size of your disc collection by replacing ‘meh’ movies in your collection with a Netflix subscription

As for the argument between “ownership” and the rental/subscription model of Netflix, as we’ve found out recently, we don’t really own the digital stuff we buy anyway. For most content you will consume, you do it once and then never again. The only reason we “buy” is to ensure that if we want to access it in the future, we have that option. And these needs can be much better served by subscription streaming, especially if your library starts to get awfully big.

The stumbling blocks to the success of streaming at the moment are things like expiring content, content being removed, and the “Balkanisation” of streamable content. The latter means that with increasing competition in the sector, and Hollywood studios starting to see the dollar signs and getting pissed off that Netflix is benefiting too much, starts to pull content from Netflix; or offer different content exclusively to different services to maximize income; or add more time delays and geographical licensing restrictions to content, or even launch their own streaming services. Instead of one place where you can get almost everything, you may then need to have several subscriptions to achieve the same. That’s the unfortunate and greed driven direction we seemed to be headed towards.

On one of these issues at least, Sarandos is working hard to change the status quo. What he wants is “ubiquitous global licencing”, where a single license allows Netflix the right to distribute all around the world. It is what Netflix is doing with its own original content, making it available everywhere, and it’s their attempt to start a new trend that they hope Hollywood will warm to, even if it may take years. I won’t be holding my breath.

In further Netflix news, a new NPD study has revealed that within a year, there will be more streaming player in the US than Blu-ray players. Of all the streaming services, Netflix remains the leader, with 40% of all connected TV users using Netflix, compared to only 17% that use YouTube and 11% that use Hulu Plus.

An interesting new trend also appears to be developing, with dedicated streaming media players like Apple TV or Roku becoming more popular. NPD puts it down to these devices being optimized for streaming content delivery, as opposed to the streaming functions of connected devices like Blu-ray players and TVs, whose implementations are often best described as an “afterthought”.

In a different study, it was found that gamers in the US are spending a quarter of the time streaming videos on their consoles. Devices like game consoles, Blu-ray players and connected TVs are the gateway devices for streaming, and their prevalence in people’s home can explain why streaming is going from strength to strength.

——

The meta moment of the week goes to the developers of business simulation game ‘Game Dev Tycoon’, for adding a novel anti-piracy feature into their game: pirate the game, and you get piracy inside the game!

The game tasks the player to create and run their own game development company. Trying to highlight the problem of piracy, one of the makers of the game, Patrick Klug, posted a special “cracked” version of the game on a popular BitTorrent website. Within a day, nearly 94% of all those playing the game were using the pirated version.

But gamers of the pirated version soon started noticing that they would be getting an unfair amount of piracy for the virtual games produced by their virtual game companies, to the point where their companies would go bankrupt. It appears they have just been punked by Klug. Klug says his deliberate release of a crippled “pirated” version of his game was an attempt to educated pirates, to hold “a mirror in front of them and showing them what piracy can do to game developers”.

A novel approach to anti-piracy, but perhaps an even more novel approach to promoting the game. Had Klug not uploaded the “sabotaged” pirated version, it’s unlikely Game Dev Tycoon would be making the news headlines as it did this week, and even more unlikely for the game to have so many players (even if 94% didn’t pay for it). This is actually more akin to a demo disguised as a pirated version, and there may be something to this approach if Game Dev Tycoon’s sales increase because of this little stunt.

Most funny was the way some pirates reported the problem. One even asked if there was a way to research “DRM” in the game so that the piracy plague could be stopped, while another lamented the fact that far too many people were pirating his virtual creations, not aware of the delicious irony contained within the statement.

I don’t know if Game Dev Tycoon features an option to research DRM in the game or not, but if it does, I hope the game doesn’t actually reward the player for doing it. Doing so would perpetuate the myth that DRM actually stops or reduces piracy, as in most cases, it does not.

What is does is to punish paying customers, while doing very little to hinder the efforts of hardcore pirates and crackers. It may also help publishers and device makers to lock up market share, which just piles on more pain for the paying customer.

So when sci-fi publisher Tor decided to make all of its ebooks DRM free about a year ago, it was a breath of fresh air that the ebook industry needed. Here was an imprint that belongs to publishing behemoth Macmillan ditching the accepted notion that you have to have DRM. The move itself was bold and risky, but made more palatable by the fact that authors and readers, not to mention bloggers and commentators such as myself, were all in full support of the move.

The only doubt left was whether the move would lead to an avalanche of piracy for Tor ebooks, now that they’ve become so easily to share and copy online.

The resulting piracy wave? Nothing. Nada. Or in Tor’s own words, “no discernible increase in piracy”. The only response have been hugely positive ones from readers and authors, praising Tor for having the guts to do the right thing.

But is anybody really surprised though at the results of this DRM-free experiment? You take something that doesn’t work, and everybody hates, and you just sort of, ah, chuck it away. Chop it off. Smash it to bits. And guess what? You end up with a better product!

People who pirate will still pirate, and the source may now be a DRM-free Tor ebook, but all that’s changed from before was perhaps the trivial step of somebody removing the DRM before sharing. It has perhaps made the life of one pirate distributor easier by a tiny bit, but it would have made no difference to people downloading. Hence “no discernible increase in piracy”.

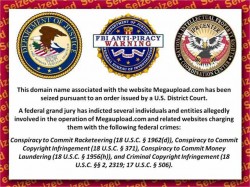

The only other argument that people could have made against Tor’s move was one of moral hazard. That even if DRM was ineffective, it was a message to people out there that piracy is not being tolerated. The problem with this argument is that people don’t care, and by the time somebody downloads a pirated copy, the DRM would have been long gone and they may never have been aware of its existence in the first place. It’s like those “don’t pirate this movie” messages you only see at the start of legally purchased DVDs, but never on pirated ones (which made the pirated ones a better product for not making you sit through the un-skippable nonsense).

That’s it for the week. Hope you enjoyed this issue of the WNR. I’ll go back to finishing watching Hotel Rwanda and then a couple of episodes of The Shield – all with no discs loading involved. See you next week.